In October 1982, I flew from New York to Copenhagen to interview Leonard Weisgard for my biography of his close friend and frequent collaborator, Margaret Wise Brown. At the time of our meeting, I had only recently begun researching Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon. I had been “passed on” to Leonard, who was retired and rarely granted interviews, by another of his (and Margaret’s) old friends, the illustrator Clement Hurd, who in turn had seen me on the recommendation of a third Brown friend who had noticed my Author’s Query in the New York Times Book Review. A biographer’s work is an incredibly chancy as well as absorbing, mystery-laden business: Had any one of the three friends broken the chain, I doubt I would have found the material needed to write my book, especially as Brown herself had died thirty years earlier, at the age of 42, of an embolism following routine surgery. Brown’s papers and effects had, in the mean time, scattered to the four winds.

Leonard had very graciously extended an open-ended invitation to me to come to Denmark whenever I wanted, for as long I wanted. Whatever initial nervousness that I as a novice biographer felt in anticipation of the momentous encounter was quickly put to rest by Leonard and his wife Phyllis, who welcomed me into their beautiful home, with its old-fashioned thatched roof, half-timber walls, and contemplative interior courtyard. I stayed with the Weisgards for eleven days, during which time Leonard and I, and sometimes Phyllis too, talked for hours at a stretch, with time out for memorable excursions in and around Copenhagen, including visits with Leonard and Phyllis’s children and friends. Rather than use a tape recorder, I kept a notebook in which, each evening, I recorded details of the day’s conversations. The following are excerpts:

MWB said to LW: “You speak as though you were translating from another language.” She would become exasperated by the slightly halting way in which he expressed his thoughts. LW says he has always found speaking about his ideas a little difficult.

*

MWB poked fun at the “easy-to-read” school of children’s literature because she thought there ought to be some mystery in the words children read in their books.

*

LW first met MWB in the basement of [publisher William R.] Scott’s house, which served as the publishing company’s office. The room was full of beautiful early American Windsor chairs. LW’s agent had put him in touch with Scott about possibly illustrating [Gertrude Stein’s children’s book] The World Is Round. MWB and he talked for hours. He was given a copy of Stein’s manuscript to read. LW told MWB about the books he read as a child – a collection of Mother Goose rhymes, for instance, which was poorly illustrated. He spoke about the sentimental “strawberries and cream” school of children’s illustration, which they agreed had no backbone. During one of their first conversations he also spoke about Julian Huxley’s writings on animal language and animal perception. This conversation became the inspiration for The Noisy Book.

Bank Street children had class between nine and twelve. LW remembers going with MWB to the nursery school to work on The Noisy Book – they did this a few times, to test the book and see if it got the children’s approval. LW says the children were atypical — hyper-intelligent and sophisticated — so that perhaps their reactions were not really a fair measure of children’s responses to the book.

There were about 20 children in the group, all sitting in low chairs and MWB would read, also sitting in a low chair as was LW, who would hold up each picture as it came up in relation to the story.

Smoke [MWB’s first Kerry blue terrier] was also there and Smoke contributed something to the situation because it made a certain impression on the children that here was this woman who came to talk with them and brought her dog. Margaret made herself into a listener, a “receiver” in the presence of the children. She did not try to outfox them to their face and she never spoke down to them. It was in the air at Bank Street that children were people like anyone else and as a result there was a deep rapport between the children and adults that could be taken for granted.

One of the children asked LW and MWB about The Noisy Book: “How much money do you think you’ll make from this book?” These children were very sharp and worldly-wise. Many of their comments about the pictures and text were incorporated into the final version. The children called MWB “Brownie.”

*

MWB felt very passionately about spring and would go south each year at the very beginning of spring and drive north, following the onset of the season all the way up to Maine.

In Maine something about her would be liberated and her face somehow changed and she would become animated in a way she wasn’t elsewhere.

When she was feeling mischievous, MWB would wrinkle up her eyes and when she wrote she also did this but with an intense concentration that did not seem mischievous but very serious, as though she were pulling the words from inside her.

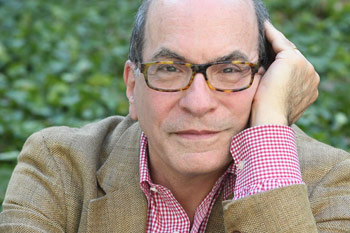

copyright © Leonard S. Marcus

Leonard S. Marcus is one of the world’s most respected historians and critics of children’s literature and illustration. He is the author of Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon and Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom, and is a trustee of The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art.